There are many natural disasters, but flooding is the most common. It is the most likely to strike industrialized and developing countries at the same rate. (1) Flooding increases the health risk of any population in a direct and indirect manner. Deaths from drowning, electrocution, building and infrastructural collapses are the most likely flood related deaths. One must keep in mind that floods can also increase the contamination of water by waterborne diseases such as vibriosis, tetanus, giardiasis, typhoid fever, cryptosporidiosis, hepatitis A, noroviruses, leptospirosis and vector-borne illnesses such as malaria, dengue fever. (1)

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one of the worst health risks that are accompanied by flooding are contaminated water sources. This can lead to infection by waterborne diseases because of direct contact and /or the drinking of contaminated waters. After a natural disaster such as a flood, the potential for an outbreak of a communicable disease increases. (1) Interventions to deter the spread of the diseases must be implemented after a disaster.

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

In the article Epidemics after Natural Disasters, the authors infer that the connection between a natural disaster and transmissible diseases is often misunderstood. It is assumed that the risk for an epidemic is increased in the confusion that is left post-disaster. Mostly, this uncertainty is due to the assumed association about dead bodies and transmissible diseases. (2)

Watson, J. T., Gayer, M., & Connolly, M. A. (2007). Epidemics after Natural Disasters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(1), 1.

Nevertheless, the increased risk factors for an epidemic after disasters are mostly linked to residents traveling or being sent to another region in search of shelter and support. The authors also make note of:

- Health status of the residents

- Accessibility of clean water and providing a clean environment

- Crowdedness of the site

- The standing health of the residents, and the accessibility to healthcare amenities.

Watson, J. T., Gayer, M., & Connolly, M. A. (2007). Epidemics after Natural Disasters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(1), 1.

In the article, the researchers outline the risk factors for outbreaks after a disaster. They reviewed the communicable diseases likely to be important and established protocols to address communicable diseases in disaster settings. It is crucial that control measures be put in place quickly if any inclination of epidemic-prone illnesses is noticed. (2)

Watson, J. T., Gayer, M., & Connolly, M. A. (2007). Epidemics after Natural Disasters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(1), 1.

Once the diseases are discovered, disaster response agencies must document the effects of the diseases and the measures that were put into place to calculate the risks of post-disaster outbreaks. (2) There are many potential dangers lurking in flood waters. People walking or swimming in the flood waters may cut themselves on debris or be bitten by animals caught in the flood such as snakes, dogs, rats or raccoons. (1) Open wounds that contact the flood waters could become infected with waterborne pathogens. Injuries to soft tissue can get infected from splashing or being in the contaminated waters if not properly covered. (1)

Watson, J. T., Gayer, M., & Connolly, M. A. (2007). Epidemics after Natural Disasters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(1), 1.

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

The only epidemic-prone infection which can be transmitted directly from contaminated water is leptospirosis, a zoonotic bacterial disease. (1) Transmission occurs through contact of the skin and mucous membranes with water, damp soil, vegetation or mud contaminated with rodent urine. (1)

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

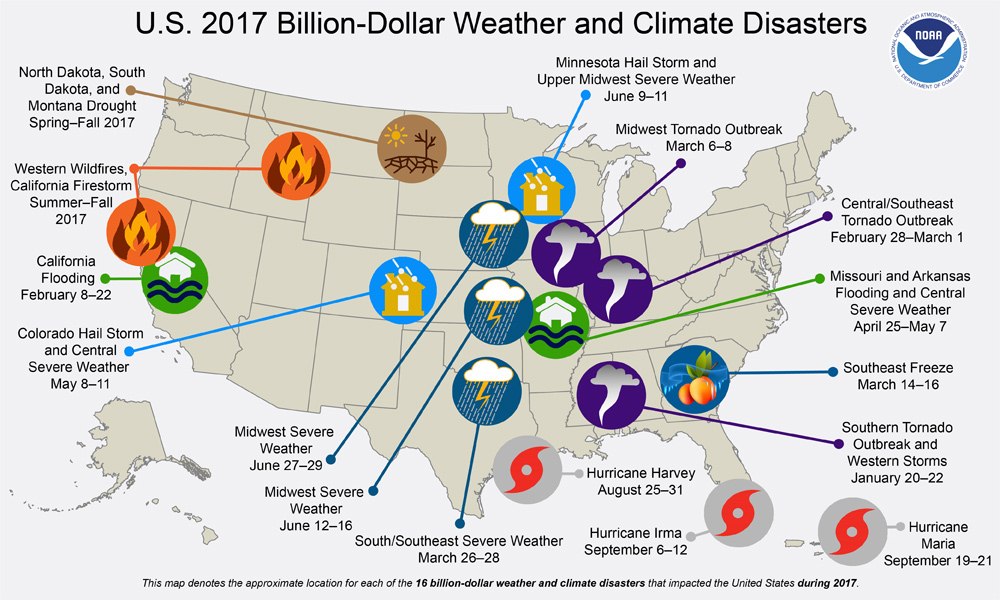

Figure 1

Incidents and Trends of Waterborne Diseases:

- It is estimated that 100-150 Leptospirosis cases are identified annually in the United States. Most cases occur in Puerto Rico & Hawaii.

- The largest recorded U.S. outbreak occurred in 1998, when 774 people were exposed to the disease. Of these, 112 became infected.

- Although incidents in the United States is relatively low, Leptospirosis is the most widespread zoonotic disease in the world.

- It’s estimated that more than 1 million cases occur worldwide each year, including about 59,000 deaths (4).

Healthcare Workers | Leptospirosis | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 1].Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/health_care_workers/index.html

- During 2013–2014, a total of 41 drinking water–associated outbreaks were reported to CDC, resulting in at least 1,005 cases of illness, 125 hospitalizations, and 12 deaths.

- From 2009 through 2015, a total of 197 cases and 16 deaths from Tetanus were reported in the United States.

- Eight outbreaks caused by parasites resulted in 294 cases, among which 277 were caused by Cryptosporidium and 12 were caused by Giardia duodenalis.

- An estimated 5,700 cases of Typhoid Fever occur each year in the United States. Most cases (up to 75%) are acquired while traveling internationally. Typhoid fever is stillcommon in the developing world, where it affects about 21.5 million people each year.(3)

WHO | World Health Statistics 2014 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 25]. Available from:

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2014/en/

Residents walking in high waters after devastating floods in Houston suburb (Aug 2017)

Heavy rains from Hurricane Harvey caused dangerous floods in many residential areas around Houston (Aug 2017)

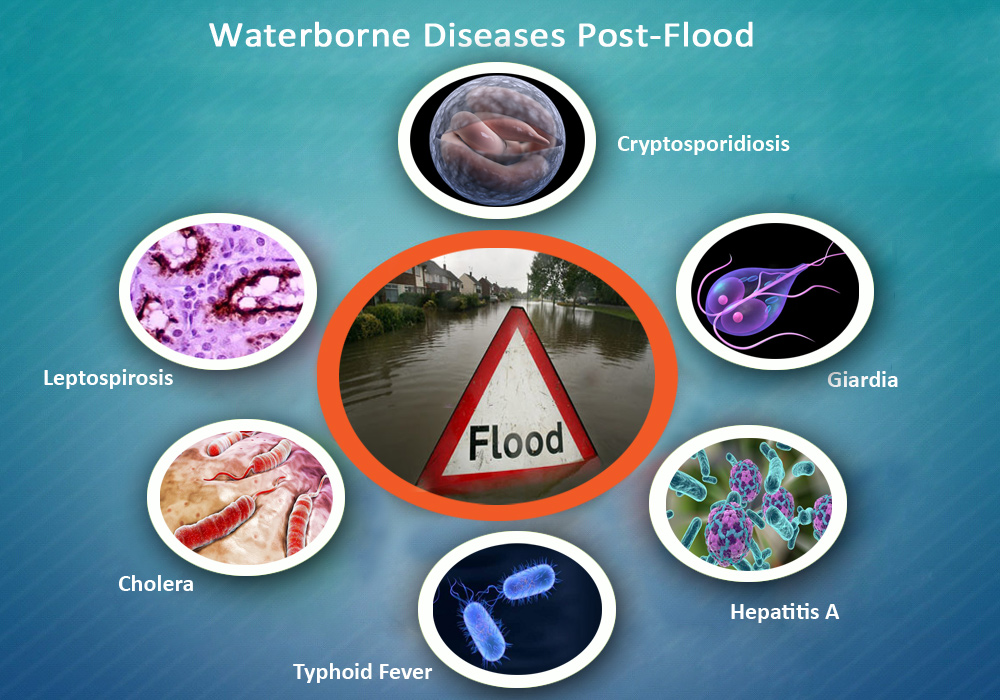

Flooding is becoming more widespread in our communities. The need to identify the signs and symptom of waterborne diseases is needed because many people from flooded regions might travel to other areas in search of shelter or family support. A flood victim may enter a healthcare center or clinic with disease symptoms. The healthcare providers need to be informed and aware of this possibility and know the signs and symptoms of various waterborne diseases that might be present in the affected population.

In the case of waterborne infections, what are the signs and symptoms of these infections and how knowledgeable are healthcare providers on the topic of these diseases?

In the following sections we will discuss some of the waterborne diseases that can be encountered after a torrential flood and how to recognize, treat and prevent them:

- Leptospirosis

- Cholera

- Typhoid Fever

- Hepatitis A

- Giardia

- Cryptosporidiosis

Figure 2

Waterborne Diseases Post-Flood

Resource information on waterborne diseases post-flood:

Follow the links for more info:

- Leptospirosis- Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease that affects humans and animals. It is caused by bacteria of the genus Leptospira. In humans, it can cause a wide range of symptoms, some of which may be mistaken for other diseases. Leptospirosis can cause serious illnesses such as kidney or liver failure, meningitis, difficulty breathing, and bleeding. (4)

https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/index.html

http://www.who.int/topics/leptospirosis/en/ - Cholera- Cholera is an acute, diarrheal illness caused by infection of the intestine with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae and is spread by ingestion of contaminated food or water. The infection is often mild or without symptoms, but sometimes it can be severe and life threatening. (5)

https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/usa/index.html

http://www.who.int/cholera/en/ - Typhoid Fever- Salmonella Typhi lives only in humans. Persons with typhoid fever carry the bacteria in their bloodstream and intestinal tract. In addition, a small number of persons, called carriers, recover from typhoid fever but continue to carry the bacteria. Both ill persons and carriers shed Salmonella Typhi in their feces. Typhoid fever is spread by the ingestion of contaminated food and water with the bacteria. (6)

https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/health-professional.html

https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/typhoid-vaccination.html

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/typhoid/en/ - Hepatitis A - Hepatitis A is a vaccine-preventable, communicable disease of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV). It is usually transmitted person-to-person through the fecal-oral route or consumption of contaminated food or water. Hepatitis A is a self-limited disease that does not result in chronic infection. (7)

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/index.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hepa/hcp/index.html

http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a - Giardiasis- Giardiasis is a diarrheal illness caused by a microscopic parasite, Giardia intestinalis (also known as Giardia lamblia or Giardia duodenalis). Once an animal or person is infected with Giardia, the parasite lives in the intestine and is passed in feces. Because the parasite is protected by an outer shell, it can survive outside the body and in the environment for long periods of time (i.e., months). (8)

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/giardia/illness.html

http://www.who.int/ith/diseases/giardiasis/en/ - Cryptosporidiosis- Cryptosporidiosis is a diarrheal disease caused by a microscopic parasite, Cryptosporidium, that can live in the intestine of humans and animals and is passed in the stool of an infected person or animal. Both the disease and the parasite are commonly known as "Crypto." The parasite is protected by an outer shell that allows it to survive outside the body for long periods of time and makes it very resistant to chlorine-based disinfectants. (9)

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/health_professionals/bwa/hospital.html

http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/4/13-119990/en/

Healthcare Workers | Leptospirosis | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/health_care_workers/index.html

General Information | Cholera | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/general/index.html

General Information | Typhoid Fever | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/sources.html

Hepatitis A [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from:

http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a

General Information| Giardia | Parasites | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1].Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/giardia/general-info.html

Parasites - Cryptosporidium (also known as “Crypto”) | Cryptosporidium | Parasites | CDC [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/index.html

Figure 3

| Disease | Mode of Transmission | Symptoms | Diagnosis/Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptospirosis bacterium of genus Leptospira | Enters the body through mucous membrane exposure to or ingestion of contaminated fresh water. The water becomes contaminated via passage of the spirochetes from the urinary tract of an infected mammalian host. | Headaches, chills, muscle aches, and jaundice warrant a high index of suspicion, and early antibiotic treatment is indicated. | Diagnosis

Serologic testing. Microscopic agglutination (MAT), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indirect hemagglutination antibody (IHA) – MAT has highest specificity Treatment Doxycycline (outpatients) or ampicillin/sulbactam (Unasyn; inpatients) |

| Cholera bacterium Vibrio cholerae |

Drinking water or eating food contaminated with the cholera bacterium. In an epidemic, the source of the contamination is usually the feces of an infected person that contaminates water and/or food. | Severe diarrhea with dehydration; abrupt onset and absence of blood in stool. Vomiting, fever, headache.

Incubation period 9-25 hours. Watery diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, wound infections, bacteremia. Vomiting, fever, headache. Wound infections may progress quickly to systemic illness and sepsis. |

Vibrio cholerae serotype 01

Diagnosis Stool cultures on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose media. Darkfield microscopy. Serotyping. Treatment Supportive care, oral or IV rehydration. Antibiotics shorten course and decrease stool volume; tetracycline, doxycycline. Vibrio cholerae non-01 serotype Diagnosis Stool cultures. Darkfield microscopy. Serotyping. Treatment Supportive care, oral or IV rehydration. Antibiotics shorten course and decrease stool volume; tetracycline, doxycycline. |

| Typhoid Fever bacterium Salmonella typhi |

Eating food or drinking beverages that have been handled by a person who is shedding Salmonella Typhi or if sewage contaminated with Salmonella Typhi bacteria gets into the water used for drinking or washing food. | Incubation period 7-14 days. Fever 75%-100% of patients, increasing in stepwise fashion; diarrhea, constipation; also cough, conjunctivitis, rose spots. 10%-20% with bloody diarrhea and severe intestinal hemorrhage in 2%. 1%-5% become chronic carriers. | Diagnosis

Multiple blood cultures (73%-97%) positive; also, urine, stool cultures, bone marrow biopsy. Uncomplicated Typhoid Fever Treatment Supportive care, oral or IV rehydration. Ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin 7.5 mg/kg po bid x 5-7 days adult Chloramphenicol 12.5 mg/kg po qid x 14-21 days Amoxicillin 25 mg/kg po tid x 10-14 days TMP/SMX 4/20 mg/kg bid x 10-14 days Complicated Typhoid Fever Treatment Ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin 7.5 mg/kg IV q 12 h x 10-14 days adult Chloramphenicol 25 mg/kg q 6h IV x 14-21 days Ampicillin 25 mg/kg q 6h IV x 10-14 days TMP/SMX 4/20 mg/kg IV q 12 h x 14 days |

| Information from references 1 through 9. | |||

| Disease | Mode of Transmission | Symptoms | Diagnosis/Treatments |

| Hepatitis A Hepatitis A virus (HAV) |

It is usually transmitted person-to-person through the fecal-oral route or consumption of contaminated food or water. Hepatitis A is a self-limited disease that does not result in chronic infection. | Incubation period 28 days average; range 15-50 days. Viral shedding 2 weeks prior to onset of jaundice. Jaundice 70% of patients, abdominal pain, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, fever. Self-limited illness; 15% with relapsing symptoms 6-9 months. | Diagnosis

Serology testing positive for IgM antibody to capsid proteins of hepatitis A (anti-IgM HAV) 5-10 days after onset of jaundice up to 6 mos. IgG antibody to HAV (anti-IgG HAV) positive early in course, confers lifetime immunity. Treatment Treatment is supportive. Vaccine available for prevention. |

| Giardia Protozoan Giardia intestinalis |

Transmission through accidental ingestion can occur if a water source has been contaminated with feces from an infected animal/person. Recreational fresh water is a highly effective means of transmission because of the ability of Giardia oocysts to survive for up to several months. In addition, oocysts are moderately chlorine resistant and can survive in treated swimming pools and hot tubs. Ingestion of a single oocyst can cause symptoms; conversely, about one-half of infected persons are asymptomatic. | Abdominal cramps, arthralgias, diarrhea, hives, nausea, pruritus, and vomiting | Diagnosis

Stool microscopy or antigen detection immunoassays Treatment Metronidazole 250 mg po tid x 5-7 days adult; 5 mg/kg po tid x 7 days pediatric Furazolidone 100 mg po qid x 10-14 days adult; 2 mg/kg po x 10 days pediatric Quinacrine 100 mg po tid x 5-7 days adult; 2 mg/kg po tid x 7 days pediatric Albendazole 400 mg po qd x 5 days adult; 15 mg/kg/day po x 5-7 days pediatric (400 mg max dose) Paromomycin 500 mg po tid x 5-7 days adult; 30 mg/kg/day po in 3 doses x 5-10 days pediatric Tinidazole 2 g po single dose adult; 50 mg/kg po single dose pediatric (2 g max) |

| Cryptosporidiosis Protozoan Cryptosporidium parvum | Ingestion of oocysts are the source of infection in humans and can survive for more than 10 days in water. CDC-recommended levels for chlorine (1 to 3 mg per L) and pH (7.2 to 7.8). Oocysts may be found in untreated recreational fresh water as well. | Incubation period 2-10 days. Watery diarrhea, dehydration, weight loss, stomach cramps, fever, nausea, vomiting. Oocysts excreted for up to 30 days while symptomatic. Self-limited illness lasting 1-2 week in immune-intact patients. Risk of complications increased in immunocompromised patients. | Diagnosis

Stool cultures. Cryptosporidium must be specifically requested; direct microscopy; DFA or IFA; EIA; PCR of tissue samples if available. Treatment Supportive care, oral or IV rehydration. Nitazoxanide 500 mg po bid x 3 days adult; 100 mg po bid x 3 day with food pediatric age 1-4; 200 mg po bid x 3 day with food pediatric age 5-11; >11 as for adults Paromomycin 500-750 mg po tid/qid or 1 g po bid adult; 25 mg/kg/day po in 3 doses pediatric Azithromycin 500 mg po q day adult |

| Information from references 10 through 14. | |||

Hurricane Katrina (Aug 2005)

Conclusion:

The climate changes that we are experiencing in our ecological system put us at risk of experiencing natural disasters such as floods, torrential rains and hurricanes. Flooding and the probability of water supply contamination increases the risk of waterborne illnesses in our communities. Healthcare providers must be able to identify, treat and educate the patients about the risks of contamination.

A long-term goal for this educational website includes increased commitment to the program and providing education regarding waterborne infections. This educational resource for healthcare providers focuses on the emergence of post flood waterborne illnesses. This website will have a positive impact on the assessment skills and quality of care provided by healthcare workers. The findings may further illuminate methods to improve instructional designs for future post-flood infectious disease education.

About me:

My name is Luva Reeves, I am a Doctor of Nursing Practice candidate at Wagner College School of Nursing in Staten Island, New York. Also, I am a Board Certified Family Nurse Practitioner licensed in New York State. The objective of this website is to offer a resource tool that will enhance the knowledge of healthcare providers regarding the recommendations set by The Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Health Safety Network (NHSN). Additionally, this website aims to delineate the signs, symptoms, surveillance, and management of commonly occurring waterborne illnesses that can arise in a post-flood community.

Resources:

- WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov1]. Available from:

http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/ems/flood_cds/en/ - Watson, J. T., Gayer, M., & Connolly, M. A. (2007). Epidemics after Natural Disasters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(1),

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2725828/ - WHO | World Health Statistics 2014 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 25]. Available from:

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2014/en/ - Healthcare Workers | Leptospirosis | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 1].Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/health_care_workers/index.html - General Information | Cholera | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/general/index.html

- General Information | Typhoid Fever | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from:https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/sources.html

- Hepatitis A [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a

- General Information| Giardia | Parasites | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1].Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/giardia/general-info.html

- Parasites - Cryptosporidium (also known as “Crypto”) | Cryptosporidium | Parasites| CDC [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/index.html

- Bross MH, Soch K, Morales R, Mitchell RB. Vibrio vulnificus infection: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(4):539–544.

- Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, et al.; Peru-United States Leptospirosis Consortium. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(12):757– 771.

- Brunette, Gary W. (ed), CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012. The Yellow Book, chapter 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976901-8 (2011).Content source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ)

- General Information | Cholera | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/general/index.html

- Waterborne Illnesses [Internet]. Medscape. [cited 2018 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/522765

- General Information | Typhoid Fever | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/sources.html

- Lynch M, Painter J, Woodruff R, Braden C; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for foodborne-disease outbreaks—United States, 1998–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(10):1–42.

- Washington State Department of Health. Waterborne disease outbreaks. August 2016. http://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/5100/420-044-Guideline-WaterOutbreak.pdf. Accessed February 7, 2017.

- Shields JM, Hill VR, Arrowood MJ, Beach MJ. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum under chlorinated recreational water conditions. J Water Health.2008;6(4):513–520.

- Carmena D. Waterborne transmission of Cryptosporidium and Giardia: detection,surveillance and implications for public health. In: Mendez-Vilas A, ed. Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology. 2010 ed., vol. 1. Badajoz, Spain: Formatex Research Center; 2010:3–14.

- Hepatitis A Information | Division of Viral Hepatitis | CDC [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/index.htm

- Leitch GJ, He Q. Cryptosporidiosis–an overview. J Biomed Res. 2012;25(1):1–16.

- Fox LM, Saravolatz LD. Nitazoxanide: a new thiazolide antiparasitic agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(8):1173–1180.

- Yoder JS, Harral C, Beach MJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).Giardiasis surveillance—United States, 2006–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(6):15–25.

Diseases links:

- 1a. WHO | Leptospirosis [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/leptospirosis/en/

- 1b. Leptospirosis | CDC [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/index.html

- 2a. WHO | Cholera [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cholera/en/

- 2b. Cholera in the United States | Cholera | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/usa/index.html

- 3a. For Healthcare Professionals | Typhoid Fever | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/health-professional.html

- 3b. Vaccination | Typhoid Fever | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/typhoid-vaccination.html

- 3c. WHO | Typhoid [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/typhoid/en/

- 4a. Hepatitis A Information | Division of Viral Hepatitis | CDC [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/index.htm

- 4b. Hepatitis A Vaccination | For Healthcare Providers | CDC [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hepa/hcp/index.html

- 4c. Hepatitis A [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a

- Illness & Symptoms| Giardia | Parasites | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/giardia/illness.html

- 5b. WHO | Giardiasis [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ith/diseases/giardiasis/en/

- 6a. Prevention C-C for DC and. CDC - Cryptosporidiosis - Public Health Activities - Boil Water Advisories - Hospitals, Health Care Facilities & Nursing Homes. [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/health_professionals/bwa/hospital.html

- 6b. WHO | Preventing cryptosporidiosis: the need for safe drinking water [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/4/13-119990/en/

Figures Resources:

- 2017 U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters: a historic year in context | NOAA Climate.gov [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2017-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historic-year

- Waterborne Diseases Post Flood, created 2018 Aug 09.

- Flood Related Waterborne Infectious Diseases, created 2018 Jul 31.